Response to Change: Homeostasis

- Homeostasis is the control or regulation of the internal conditions of a cell or organism

- Some examples of these internal conditions include:

- Water content (of an individual cell or of the body fluids of an organism)

- Temperature

- pH

- Blood pressure

- Blood glucose concentration

- It is important for an organism to keep these internal conditions within set limits to ensure they stay healthy and to maintain optimum conditions to allow the organism to function in response to internal and external changes

- If these limits are exceeded, the organism may die

- Homeostasis maintains optimal conditions for enzyme action and all cell functions

- This ensures that reactions in body cells can function and therefore the organism as a whole can live

- Two examples of homeostasis in humans include the control of body temperature and the control of body water content

Control of body temperature in humans

- The core body temperature of humans is kept close to 37°C

- This is very tightly controlled as a change in core body temperature of more than 2°C can be fatal

- One reason for this is that such a temperature change would stop essential enzymes from functioning optimally

- For this reason, the human body must be able to make a coordinated response to any rise or fall in body temperature

- Body temperature is monitored and controlled by the thermoregulatory centre in the base of the brain as blood passes through it

- The thermoregulatory centre contains receptors that are sensitive to the temperature of the blood

- The skin also contains temperature receptors and sends nervous impulses to the thermoregulatory centre

- The brain then coordinates a cooling or heating response, depending on what is required

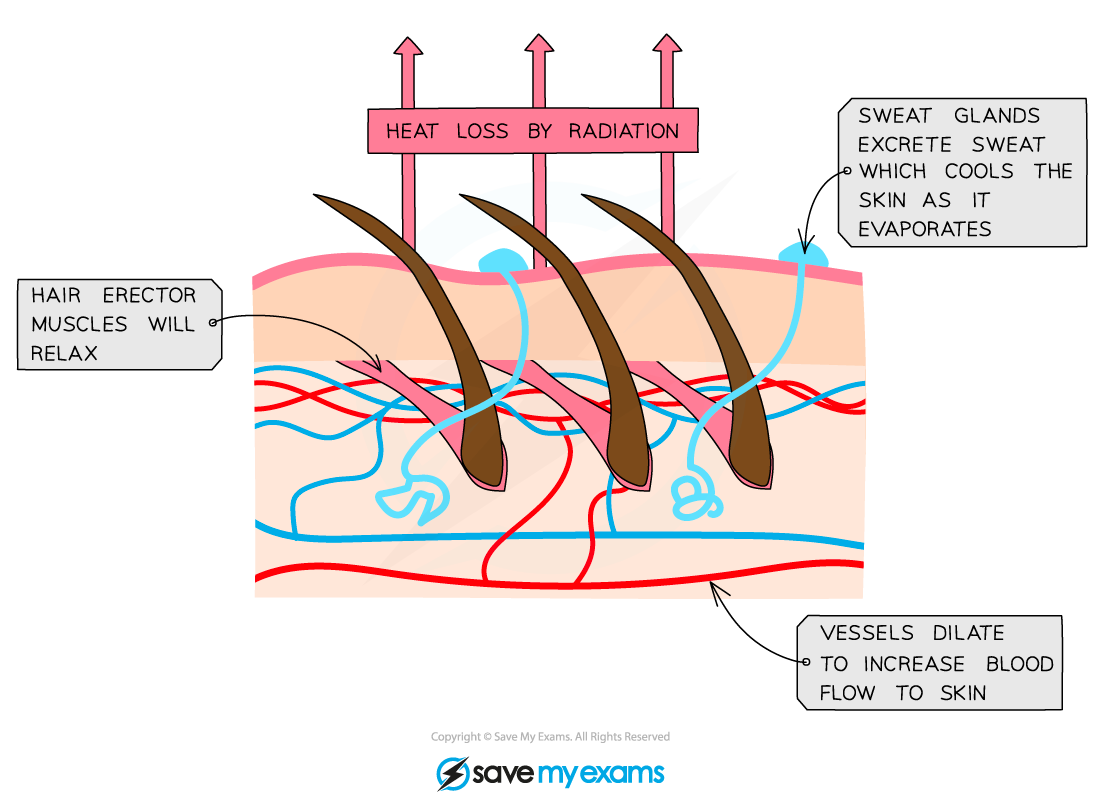

Cooling mechanisms in humans

- Vasodilation of skin capillaries

- Heat exchange (both during warming and cooling) occurs at the body's surface as this is where the blood comes into closest proximity to the environment

- One way to increase heat loss is to supply the capillaries in the skin with a greater volume of blood, which then loses heat to the environment via radiation

- Arterioles (small vessels that connect arteries to capillaries) have muscles in their walls that can relax or contract to allow more or less blood to flow through them

- During vasodilation, these muscles relax, causing the arterioles near the skin to dilate and allowing more blood to flow through capillaries

- This is why pale-skinned people go red when they are hot

- Sweating

- Sweat is secreted by sweat glands

- This cools the skin by evaporation which uses heat energy from the body to convert liquid water into water vapour

- Flattening of hairs

- The hair erector muscles in the skin relax, causing hairs to lie flat

- This stops them from forming an insulating layer by trapping air and allows air to circulate over skin and heat to leave by radiation

Responses in the skin when the body temperature is too high and needs to decrease

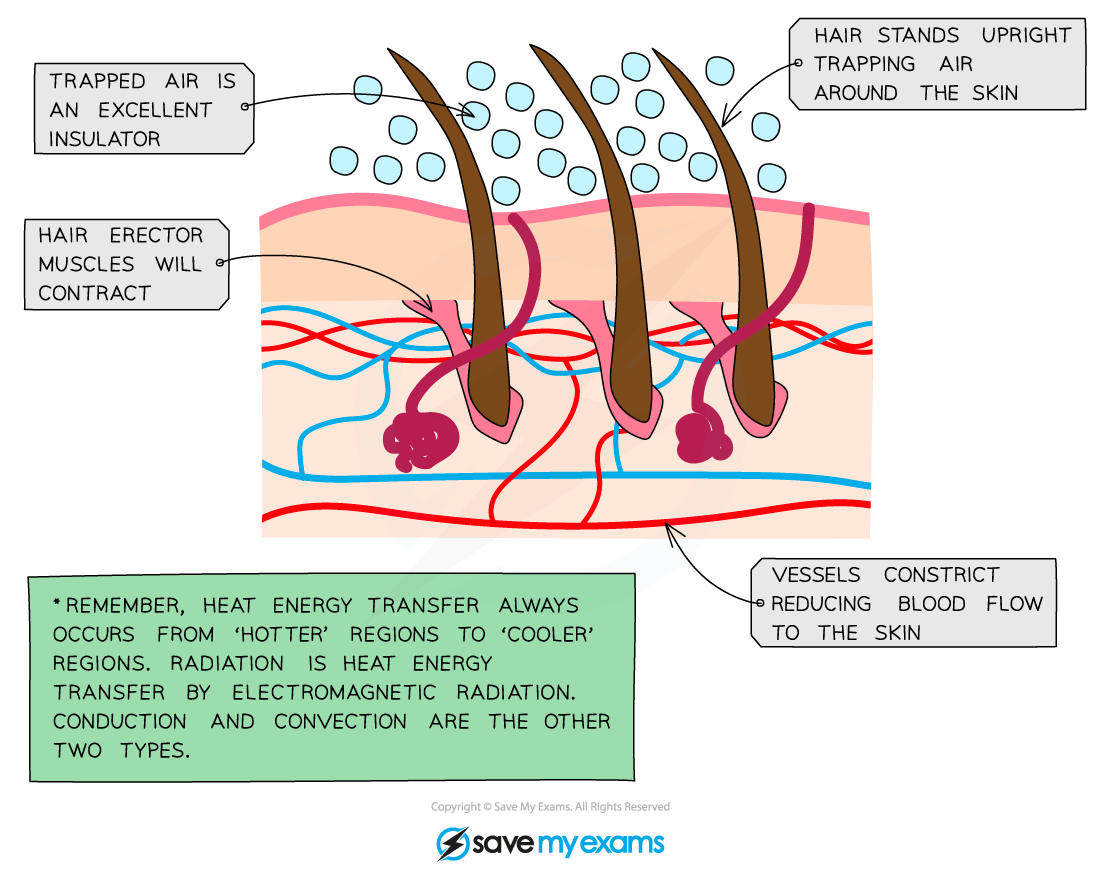

Warming mechanisms in humans

- Vasoconstriction of skin capillaries

- One way to decrease heat loss is to supply the capillaries in the skin with a smaller volume of blood, minimising the loss of heat to the environment via radiation

- During vasoconstriction, the muscles in the arteriole walls contract, causing the arterioles near the skin to constrict and allowing less blood to flow through capillaries

- Vasoconstriction is not, strictly speaking, a 'warming' mechanism as it does not raise the temperature of the blood but instead reduces heat loss from the blood as it flows through the skin

- Shivering

- This is a reflex action in response to a decrease in core body temperature

- Muscles contract in a rapid and regular manner

- The metabolic reactions required to power this shivering generate sufficient heat to warm the blood and raise the core body temperature

- Erection of hairs

- The hair erector muscles in the skin contract, causing hairs to stand on end

- This forms an insulating layer over the skin's surface by trapping air between the hairs and stops heat from being lost by radiation

Responses in the skin when body temperature is too low and needs to increase

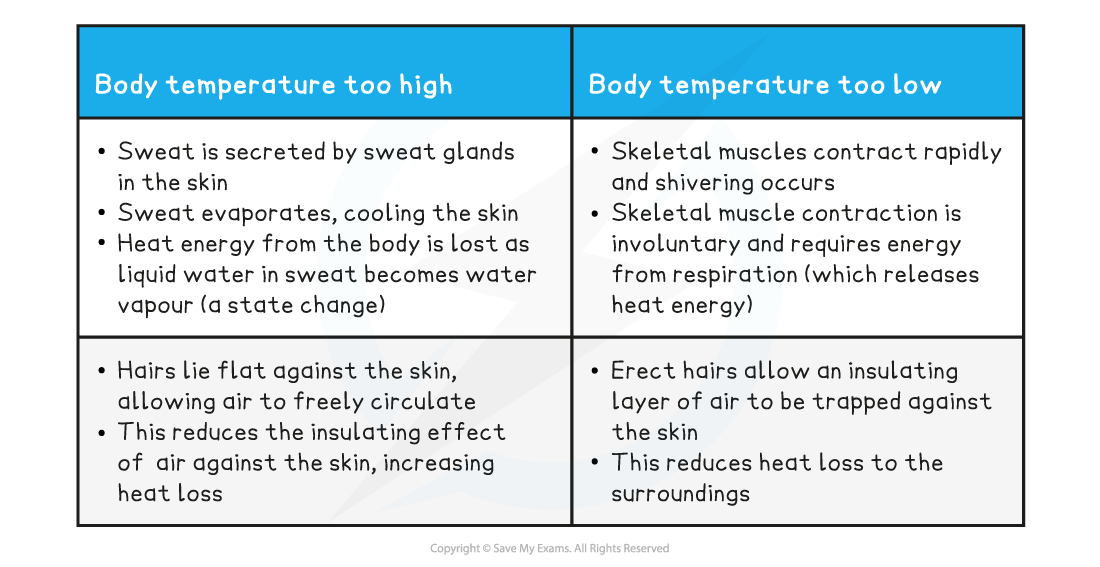

Body Temperature Control Summary Table

Control of body water content in humans

- Water loss via the lungs (during breathing) or skin (during sweating) cannot be controlled, but the volume of water lost in the production of urine can be controlled by the kidneys

- The nephrons of the kidneys contain structures called tubules, through which filtrate passes on its way to the bladder

- Water can be reabsorbed from this filtrate as it passes along these tubules (known as collecting ducts)

- If the water content of the blood is too high then less water is reabsorbed, if it is too low then more water is reabsorbed

- In a similar way to blood temperature being monitored, blood water content is detected by receptors in the base of the brain as blood passes through it

- The pituitary gland in the brain constantly releases a hormone called ADH (antidiuretic hormone)

- ADH affects the permeability of the collecting ducts to water

- The quantity of ADH released depends on how much water the kidneys need to reabsorb from the filtrate

- If the water content of the blood falls below a certain level:

- The blood is too concentrated

- Receptors detect this and stimulate the pituitary gland to release more ADH

- This causes the collecting ducts of the nephrons to become more permeable to water

- This leads to more water being reabsorbed from the collecting ducts

- The kidneys produce a smaller volume of urine that is more concentrated (contains less water)

- If the water content of the blood rises above a certain level:

- The blood is too dilute

- Receptors detect this and stimulate the pituitary gland to release less ADH

- This causes the collecting ducts of the nephrons to become less permeable to water

- This leads to less water being reabsorbed from the collecting ducts

- The kidneys produce a larger volume of urine that is less concentrated (contains more water)

转载自savemyexam