- 翰林提供学术活动、国际课程、科研项目一站式留学背景提升服务!

- 400 888 0080

John Locke 论文竞赛报名即将截止,28题可选(附获奖作品)

John Locke Essay Competition 约翰·洛克论文学术活动 是每年申请“爬藤选手”中最最热门的比赛之一,每年吸引数千名全球最擅长思考和写作的中学生参加,评委由牛津大学教授组成,往届优胜者遍布哈耶普斯牛剑等世界名校。John Locke学术活动的目的在于, 鼓励参赛的同学们通过学术写作 探索 超越自己学校课程的 各种富有挑战性且有趣的问题,让同学们有机会,在备赛的过程中,积累丰厚的知识,培养独立思考、推理能力、批判性分析、说服力等综合能力, 提高写作的论证技巧。

适合对象:

全球18岁以下对英美学术写作感兴趣的同学们均可参加。比赛分为15岁-18岁的高年级组和15岁以下的低年级组。

比赛时间:

作品提交截止日期:2022年6月30日

2022年7月14日,通知入围候选人

2022年8月27日,低年级组颁奖晚宴

2022年9月3日,经济组获颁奖晚宴

2022年9月10日,历史组颁奖晚宴

2022年9月17日,政治组和法律组颁奖晚宴

2022年9月24日,哲学组和神学组颁奖晚宴

2022年9月30日,心理学组颁奖晚宴

比赛内容:

根据官方给出的赛题,选择一道题,完成一篇2000词以下的命题论文作品,并在线提交。

比赛题目:

高年级组(15-18岁),参赛题目涉及 哲学、政治、经济学、历史、心理学、神学、法律 7个人文社科领域,共28个可选题。

低年级组(15岁以下),参赛者的论文题目是7个有趣的跨学科话题。

【扫码联系老师领取报名表】

获取备赛计划,历年全部获奖论文,考前查缺补漏、重点冲刺

往届获奖作品

Isn't all reasoning (outside mathematics and formal logic) motivated reasoning?

Introduction

When voters vehemently defend a candidate after his or her weaknesses have been exposed, or smokers convince themselves that cigarettes are actually not as bad for their health as they appear, these instances highlight how personal preferences can generally influence beliefs. People have a tendency to reason their way to favorable conclusions, with their proclivities guiding how evidence is gathered, arguments are evaluated, and memories are recollected. These actions of reasoning are all driven by underlying motivations, leading to beliefs tinged with bias that can seem objective to the individual (Gilovich and Ross, 2016). Motivated reasoning, a phenomenon studied in social psychology, can be defined as the “tendency to find arguments in favor of conclusions we want to believe to be stronger than arguments for conclusions we do not want to believe” (Kunda, 1990). This concept often contrasts critical thinking, which is generally viewed as the rational, unbiased analysis of facts to form a judgment at the highest level of quality (Paul and Elder, 2009). In this essay, I will champion a case for motivated reasoning and in turn, prove why there is no such thing as “good” or “accurate” critical thinking. Instead, all reasoning, outside mathematics and formal logic, is essentially motivated reasoning – justifications that are most desired instead of impartially reflect the evidence.

An Evolutionary Perspective

Motivated reasoning has been a pervasive tendency of human cognition, since the beginning of time, as it is ingrained in our basic survival instincts. Evolutionarily, people have been shown to utilize motivated reasoning to confront threats to the self. Research shows that people

weighed facts differently when those facts proved to be life-threatening. In 1992, Ditto and Lopez compared study participants who’d received either positive or negative medical test results. Those who were told they’d tested positive for an enzyme associated with pancreatic disorders were more likely to believe the test was inaccurate and discredit the results (Ditto and Lopez, 1992). When it comes to our health and quality of life especially, we tend to delude ourselves. Although we may prefer that human decision making be a thoughtful and deliberative process, in reality, our motivations tip the scales to make us less likely to believe something is true if we do not wish to believe it. For instance, a study by Reed and Aspinwall found that women who were caffeine drinkers engaged in motivated reasoning when they dispelled scientific evidence that caffeine consumption was linked to fibrocystic breast disease (Reed and Aspinwall, 1998).

In addition to protecting their health, evolutionarily, humans use motivated reasoning to bolster their self-esteem and protect their self-worth. A common example of this is the self-serving bias, which is “the tendency to attribute our successes to ourselves, and our failures to others

and the situation” (Stangor, 2015). For instance, students might attribute good test results to their own capabilities, but perform motivated reasoning and make a situational attribution to explain bad test results, all the while upholding the idea that they are intelligent beings. The phenomenon of the self-serving bias is widely considered to be essential for people’s mental health and adaptive functions (Taylor and Brown, 1994). It is thought to be a universal, fundamental need of individuals for positive self-regard (Heine et al., 1999). That is, people are motivated to possess and maintain positive self-views, and in turn, minimize the negativity of their self-views – by glorifying one’s virtues and minimizing one’s weaknesses, relative to objective criteria. This basis begs the question of whether humans are truly ever able to process information in an unbiased fashion.

A Fight for Personal Beliefs

People not only interpret facts in a self-serving way when it comes to their health and well-being; research also demonstrates that we engage in motivated reasoning if the facts challenge our personal beliefs, and essentially, our moral valuation and present understanding of the world. For example, Ditto and Liu showed a link between people’s assessment of facts and their moral convictions; they found that individuals who had moral qualms about condom education were less likely to believe that condoms were an effective form of contraception (Ditto and Liu, 2016). Oftentimes, the line between factual and moral judgments become blurred in this way.

In the context of identity, there are powerful social incentives that drive people’s thought processes. People strive for consistency among their attitudes and self-images. Festinger’s cognitive dissonance theory highlights this tendency – he found that members of a group who believed in the end of the world for a predicted date became even more extreme in their views after that date had passed, in order to mitigate their cognitive dissonance (Festinger, 1962). Moreover, when it comes to voting, normatively, new negative information surrounding a preferred candidate should cause downward adjustment of an existing evaluation. However, recent studies prove that the exact opposite takes place; voters become even more supportive of a preferred candidate when faced with negatively valenced information, with motivated reasoning as the explanation for this behavior (Redlawsk et al., 2010). In a 2015 APA analysis, 41 experimental studies of bipartisan bias were examined, demonstrating that self-identified liberals and conservatives showed a robust partisan bias when assessing empirical evidence, almost to an equal degree (Weir, 2017). Additionally, neuroscience research suggests that “reasoning away contradictions is psychologically easier than revising feelings” (Redlawsk, 2011). Given the context of groupthink and one’s group identity, the bias’ prevalence is powerful and persistent. Ultimately, people are psychologically motivated to support and maintain existing evaluations, even when confronted with disconfirming information, as to take an opposing viewpoint against a group would damage one’s reputation and challenge one’s existing social identity.

The Illusion of Objectivity

With the exception of mathematics and formal logic, all reasoning, essentially, is motivated reasoning. When it comes to decision-making and critical thinking, total unbiased analysis or evaluation of factual evidence, is largely illusory. In reality, we act based on an incomplete vision, perceived through filters constructed by our individual history and personal preferences. To scientifically operate on an objective level cannot be achieved. Every second, we as humans receive and process thousands of bits of information from our environment. To consciously analyze all of the sensory stimuli would be overwhelming; thus, our brain utilizes pre-existing knowledge and memory to filter, categorize and interpret the data we receive. The brain extrapolates information it believes to be missing or eliminates those deemed extraneous, to form a considerably coherent image (Thornton, 2015). Each person has unique filters that prevent them from being unbiased, even on a granular level, to cope with life’s complexity. Whether we are aware of our biases or not, affective contagion occurs, a phenomenon where “conscious deliberation is heavily influenced by earlier, unconscious information processing” (Strickland et al., 2011).

Even in scientific journals, statistical analysis is utilized to provide a stamp of objectivity to conclusions. However, people tend to use statistical information in a motivated way, further perpetuating the illusion of objectivity. Berger and Berry argue that although objective data from an experiment can be obtained, “reaching sensible conclusions from the statistical analysis of this data requires subjective input,” and the role of subjectivity inherent in the interpretation of data should be more acknowledged (Berger and Berry, 1988). Similarly, in law, lawyers and advocates for both the prosecution and the defense utilize motivated reasoning to prove innocence or guilt. The judge’s job, on the other hand, is to eliminate motivational bias in their own assessment of evidence when drawing up a conclusion. However, the interpretation of the law can be skewed; sometimes, preferred outcomes, based on legally irrelevant factors, drive the reasoning of judges too, without their full awareness. Redding and Reppucci examined whether the sociopolitical views of state court judges motivated their judgments about the dispositive weight of evidence in death penalty cases. They found that judges’ personal views on the death penalty did indeed influence their decisions (Sood, 2013).

In the modern day, one of the greatest promises of artificial intelligence and machine learning is a world free of human biases. Scientists believed that operating by algorithm would create gender equality in the workplace or sidestep racial prejudice in policing. But studies have shown that even computers can be biased as well, especially when they learn from humans, adopting stereotypes and schemas analogous to our own. Biases can creep into algorithms; recently, ProPublica found that a criminal justice algorithm in Florida mislabeled African-American defendants as “high risk,” approximately twice the rate it mislabeled white defendants (Larson and Angwin, 2016).

Conclusion

Essentially, I demonstrate that all reasoning, aside from logic-based, is essentially motivated. Ultimately, to support preferred conclusions, people unknowingly display a bias in their cognitive processes that underlie reasoning. Even though we can never fully be rid of motivated reasoning, consistently striving towards an unbiased evaluation of facts is still key to achieving rigorous standards for decision-making. With today’s media landscape and the internet, a deviation from a purely fact-based evaluation has been amplified; it is now easier than ever to operate in an echo chamber and choose which sources of information fit one’s preferred reality. A report by Stanford’s Graduate School of Education found that students ranging from middle school to college were all poor at evaluating the quality of online information (Donald, 2016). Fake-news websites and the spread of misinformation that have proliferated in the past decade, all compound the problem. Mistrust of the media has increasingly grown to become a powerful tool for motivated reasoning. To restore our faith in facts, media literacy must take place. I champion improving existing channels of communication so that they help us to identify the roots of our biases, then encourage us to adjust our beliefs accordingly. Becoming aware of our deeply-rooted tendencies and thinking mechanisms is valuable, as it enables us to make decisions with more lucidity and transparency, and hopefully, for the betterment of our world.

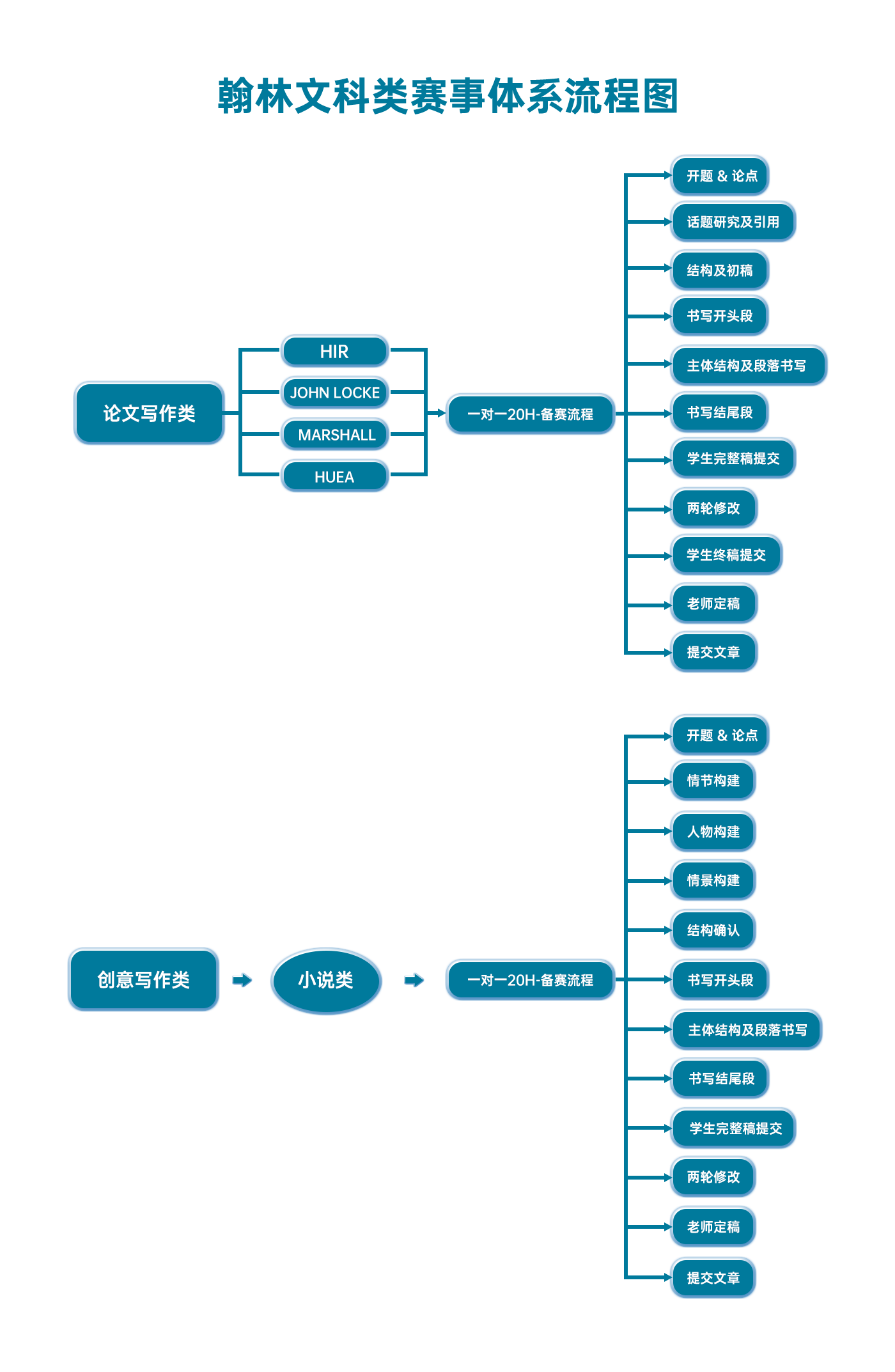

翰林文科学术活动课程体系流程图

早鸟钜惠!翰林2025暑期班课上线

最新发布

© 2025. All Rights Reserved. 沪ICP备2023009024号-1