- 翰林提供学术活动、国际课程、科研项目一站式留学背景提升服务!

- 400 888 0080

2020年John Locke论文写作竞赛神学三等奖论文全文

约翰洛克写作学术活动(John Locke)是由位于英国牛津的独立教育组织John Locke Institute与英国牛津大学和美国普林斯顿大学等名校教授合作组织的学术项目,意在考察学生在不同学科领域内的基本知识结构,议论文的基本写作格式与技巧,独立思考能力以及清晰的逻辑和辩证分析能力。以17世纪英国著名哲学家、古典自由主义鼻祖John Locke命名,是人文社科含金量最高的国际征文比赛之一。

John Locke写作比赛提供哲学、政治、经济学、历史、心理学、宗教、法律共七个领域的内容(仅限高中组,初中组题目是额外的),喜爱文科方向的学生绝对不要错过!

2022年6月30日 晚上11:59pm(GMT)

● 高年级组:15岁~18岁

● 低年级组:15岁及以下

2022年John Locke论文学术活动已经放题啦!

对其他学科领域感兴趣的同学

可扫码添加微信咨询

【免费领取】历年相关获奖论文学习

以下为2020年John Locke论文写作学术活动神学三等奖论文,对神学感兴趣的同学可以参考学习。

Is Islam a Religion of Peace?

Varun Venkatesh, Tanglin Trust School, Singapore

Third Prize for the 2020 Theology Prize | 8.5 min read

The incipit “Bismillah” initiates each Surah in the Qur'an except for the 9th, depicting Allah (swt) as a deity of compassion, peace and mercy. These ideas are reinforced throughout the Qur'an, most prominently in verses like Ayat 63 in Surah Al-Furqan:

“And the servants of the Most Merciful are those who walk upon the earth easily, and when the ignorant address them [harshly], they say [words of] peace,”

Thus, encountering verses that seem to be antithetical to the tenor of tolerance and compassion that is salient in the Qur'an can be a justifiably dissonant experience. Take Ayat 29 in Surah Al-Tawbah:

“Fight those who do not believe in Allah or in the Last Day and who do not consider unlawful what Allah and His Messenger have made unlawful and who do not adopt the religion of truth from those who were given the Scripture - [fight] until they give the jizyah willingly while they are humbled.”

This essay attempts to navigate this incongruity and categorically prove that Islam is a religion of peace, first from a theological standpoint which endeavours to contextualize and justify verses of the Qur'an oft cited as evidence of Islam’s inherent tendency towards violence. This is complemented by a pragmatic line of argumentation which demonstrates that manifestations of Islamic violence, such as terrorism, are religiously illegitimate and unrepresentative of Islam’s doctrine.

To begin with, the notion of ‘Peace’ must be elucidated: peace is defined as a state of harmony, devoid of any fear of violence. Consider a scenario wherein a harmonious community is subjected to a threat of violence by malicious agents, ergo the community is no longer in a state of peace. Modus vivendi is always preferable, but the fear of violence in this case can only be assuaged by proportional retaliation. Hence, any definition of peace would be remiss if it did not sanction violence in certain limited capacities to preserve and protect peace in the community: that is to say, peace is not tantamount to pacifism.

The concept of “jihad” must also be clarified. It is broadly defined as any personal or social struggle to conform to Allah’s (swt) guidance, further categorised into “greater” jihad, the struggle against one’s own carnal impulses, and “lesser” jihad, the use of non-peaceful means to defend the “ummah” (community) against oppression. Whatever its theological underpinning, it has unfortunately acquired more martial connotations; therefore, any reference to jihad in this essay is an allusion specifically to lesser jihad.

Under the above definition of peace, critics of Islam often cite verses from the Qur'an that, at first glance, seem to incite unprovoked jihad. Take the examples of Ayat 216 in Surah Al-Baqarah (known as the Jihad verse) and Ayat 5 in Surah at-Tawbah (known as the Sword verse):

“Fighting has been enjoined upon you while it is hateful to you. But perhaps you hate a thing and it is good for you; and perhaps you love a thing and it is bad for you. And Allah Knows, while you know not.”

“And when the sacred months have passed, then kill the polytheists wherever you find them and capture them and besiege them and sit in wait for them at every place of ambush. But if they should repent, establish prayer, and give zakah, let them [go] on their way. Indeed, Allah is Forgiving and Merciful.”

On reading these verses, an instinctive reaction is to conclude that Allah (swt) condones wanton brutality in the name of Islam. It is imperative, however, that these verses are interpreted with contextual veracity. Prophet Muhammad (saw) peacefully preached his holy teachings in Mecca for 12 years after his first revelation. As detailed in Ayat 1 in Surah at-Tawbah, there existed a treaty between the Muslims and the Mushriks of Mecca. The Meccans broke this covenant, and when given four months to make amends, further harassed and persecuted the Muslims. Due to these anti-Muslim pogroms perpetrated by the indigenous Meccan community, Prophet Muhammad (saw) and his followers were forced to undertake the first Hijrah to Medina. Even after fleeing, they were subjected to threats from the Quraysh aristocracy.1 It was only under these conditions of extreme duress that Prophet Muhammad (saw) authorized violence in self-defence against those polytheists who would accept nothing other than the eradication of Islam in Arabia, as depicted in Ayat 217 in Surah Al-Baqarah:

“Fighting therein is great [sin], but averting [people] from the way of Allah and disbelief in Him and [preventing access to] al-Masjid al-Haram and the expulsion of its people therefrom are greater [evil] in the sight of Allah. And fitnah is greater than killing.”

Moreover, even though the permission for violence was borne out of conditions of repression, there were still a host of caveats that came with it. Owing to the meticulous usage of “wa-la ta’tadu” (do not transgress) in the Qur'an, jihad is not a free license for savagery, but a tool to establish and maintain peace and justice, only sanctioned in situations of self-defense where the peace of the ummah is under threat. Concerning the treatment of the Mushriks of Mecca, the latter half of Ayat 5 in Surah at-Tawbah clearly affirms that those that honored the promise or repented their betrayal were to be spared and returned to their land. The Quran also delineates rules analogous to modern just-war theory, such as jus ad bellum and jus in bello, by outlining who is exempt from conflict, the conditions for the cessation of hostility, the treatment of prisoners of war and nonbelligerents, women and children.

Ultimately, from a theological standpoint, we can safely infer that Islam conforms closely to this essay’s definition of peace. The Qur'an does not allow for arbitrary violence: the primary goal of any call for violence must be in response to a comparable magnitude of oppression. It is only permitted to subdue any threat to the peace of the ummah, and must comply with the defined criteria, implemented to act as a bulwark against indiscriminate brutality. The accusation that Islam advocates unwarranted violence against polytheists hinges itself on an interpretation of select verses in the Quran devoid of any contextual or historical comprehension.

If Islam is judged by the actions of its followers, however, its status as a peaceful religion becomes dubious. From 1968 to 2005, Islamic terrorism was responsible for 86.9% of all casualties inflicted by terrorist groups with religious motivations.2 Terrorism might be the product of complex socio-political circumstances, but Islam’s ability to bestow upon extremism some element of legitimacy in the eyes of the lay public is irrefutable. Take the example of Osama bin Laden and his two fatwas (non-binding legal opinions on a point of Islamic law) that frequently quote the Qur'an: can they be used as evidence of violence justified by Islam?

On close inspection, bin-Laden’s fatwas suffer from a dearth of religious integrity. He engages in the decontextualization and truncation of Qur'anic verses to manipulate and convince, which dissociates the fatwas from bona-fide Islam. For example, in his 1996 fatwa, he quotes the Sword verse, but deliberately omits the aforementioned half of the Ayat that calls for mercy. bin-Laden’s intention is not interpretive veracity, but the indoctrination of his followers. He therefore manipulates the Sword verse to proclaim that there cannot be any amity with the infidels. Equally egregious omissions are committed in his 1998 fatwa, proof of his selective application of the Qur’an to support the extremist narrative.

This religious chicanery manifests itself in other ways. Consider the principle of ijtihad, which allows for independent interpretation of the Qur'an as long as the mujtahid (scholar qualified to perform ijtihad) has expertise of Arabic, theology and jurisprudence, and it propagates the will of God. In this capacity, terrorists interpret verses in the Qur'an as a premise for excessive aggression. However, ijtihad can only be applied where the Qur'an is considered ambiguous, or where there is no scholarly consensus. In the context of terrorism, neither of these conditions are fulfilled: both the Qur'an and scholastic opinion are vehemently opposed to the murder of non-combatants and groundless confrontation. An interpretation of the Qur'an that is exercised to justify unprovoked jihad has no theological validity. This conclusion is explicitly succoured by Ayat 7 in Surah Ali ‘Imran:

“It is He who has sent down to you, [O Muhammad], the Book; in it are verses [that are] precise - they are the foundation of the Book - and others unspecific. As for those in whose hearts is deviation [from truth], they will follow that of it which is unspecific, seeking discord and seeking an interpretation [suitable to them]."

The means used by terrorists are also decoupled from true Islam. Consider the issue of “istishhad” (martyrdom): in glorifying martyrdom, organizations like Al-Qaeda attract devout Muslims to suicide bombing by professing that the attainment of “shahid” is a direct path to eternal salvation. Suicide bombing thus inspires religious and idealogical zeal and is an effective method in accomplishing the objectives of extremist organizations. As such, critics of Islam are quick to point to suicide bombings as emphatic evidence of violence immanent in Islam.

However, these martyrdom operations have no religious justification. The vast majority of the ulama (“guardians, transmitters and interpreters of religious knowledge”) condemns suicide bombing attacks as fundamentally un-Islamic for numerous reasons. Firstly, suicide is considered to be anathema in Islam3: the right to life is a gift from God that followers of Islam are obliged to cherish, as noted by Ayat 195 in Surah Al-Baqarah:

“And spend in the way of Allah and do not throw [yourselves] with your [own] hands into destruction [by refraining]. And do good; indeed, Allah loves the doers of good.”

The killing of women and children makes it even harder to justify them as morally and religiously permissible in any way. An insurrectionist who kills non-combatants is guilty of “baghy” (armed transgression), a capital offence. To paraphrase Shaykh Afifi al-Akiti’s4 seminal fatwa “Defending the Transgressed”, suicide bombing should be considered a reprehensible innovation in the Islamic tradition that has consequences of eternal damnation. This is corroborated by Ayat 151 of Surah Al-An’am, an example of unambiguous Qur'anic rebuke of suicide bombers:

“And do not kill the soul which Allah has forbidden [to be killed] except by [legal] right. This has He instructed you that you may use reason."

All things considered, Islamic terrorism is in no way religiously tenable. Any attempt to vindicate it involves the selective choice of verses of the Qur'an that have been abbreviated and taken out of context, as well as erroneous interpretations of these verses whose only purpose is to bolster the extremist narrative.

It is important to reiterate that by no measure is Islam a religion of pacifism. Rather, from a theological perspective, any sanctioning of violence is accompanied by a profusion of contextual constraints and rules. In the real world, the minute percentage of Muslims who conduct terrorism in the name of Islam flout the unequivocal safeguards put in place by the Qur'an by cherry-picking halves of verses and decontextualizing them to their own end. By contravening these constraints, their actions are un-Islamic, unrepresentative of the Muslims who know their religion to be one of peace and compassion. Islam abides by the definition expressed at the start of this essay, establishing it as a religion of peace.

Consider the implications of the contrarian conclusion: to label Islam a religion of violence is to say that the vast majority of the 1.8 billion Muslims worldwide find solace and religious fulfillment in a religion that promotes and expects violence of its followers. This is a fallacious and inaccurate claim to make. Indubitably, every instance of Islamic violence is tragic and every life lost to Islamic terrorism is lamentable, but to generalize and besmirch the vast majority of Muslims who consider this violence to be abhorrent and irreconcilable with their religious identity is in no way a constructive response.

Author's Note:

Honorifics have been included and abbreviated in this essay. Subhanahu wa Taʿālā is abbreviated to (swt) and Ṣallallāhu ′alayhe wassallam is abbreviated to (saw).

Footnotes:

1 Shaikh, Fazlur Rehman (2001). Chronology of Prophetic Events. London: Ta-Ha Publishers Ltd. pp. 51–52.

2 James A. Piazza (2009) Is Islamist Terrorism More Dangerous?: An Empirical Study of Group Ideology, Organization, and Goal Structure, Terrorism and Political Violence, 21:1, 62-88

3 Hashemi, Seyed & Ajilian, Maryam & Hoseini, Bibi & Khodaei, Gholam & Saeidi, Masumeh. (2014). Youth Suicide in the World and Views of Holy Quran about Suicide. International Journal of Pediatrics. 2. 101-108.

4 Shaykh Afifi al-Akiti is a massively reputed and pre-eminent Islamic scholar and is currently the KFAS Fellow in Islamic Studies at the Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies.

Bibliography:

Piazza, J., 2009. Is Islamist Terrorism More Dangerous?: An Empirical Study of Group Ideology, Organization, and Goal Structure. Terrorism and Political Violence, 21(1), pp.62-88.

Takim, L., Jihad | Theology – University Of St. Thomas - Minnesota. [online] Stthomas.edu. Available at: <https://www.stthomas.edu/theology/encounteringislam/dialogues/jihad/#:~:text=The%20Qur'anic%20und erstanding%20of,you%2C%20but%20do%20not%20transgress.>

Holbrook, D.. Using The Qur’An To Justify Terrorist Violence: Analysing Selective Application Of The Qur’An In English-Language Militant Islamist Discourse. [online] Terrorismanalysts.com. Available at: <http://www.terrorismanalysts.com/pt/index.php/pot/article/view/104>

Lawrence, B., The Qur'an.

Murad, A., n.d. Bin Laden's Violence Is A Heresy Against Islam. [online] Web.archive.org. Available at: <https://web.archive.org/web/20100103130922/http://islamfortoday.com/murad04.htm>

al-Akiti, A., 2005. Defending The Transgressed: Mudafi' Al-Mazlum. [online] Livingislam.org. Available at: <https://www.livingislam.org/maa/dcmm_e.html>

Translation of the Quran obtained from https://quran.com/

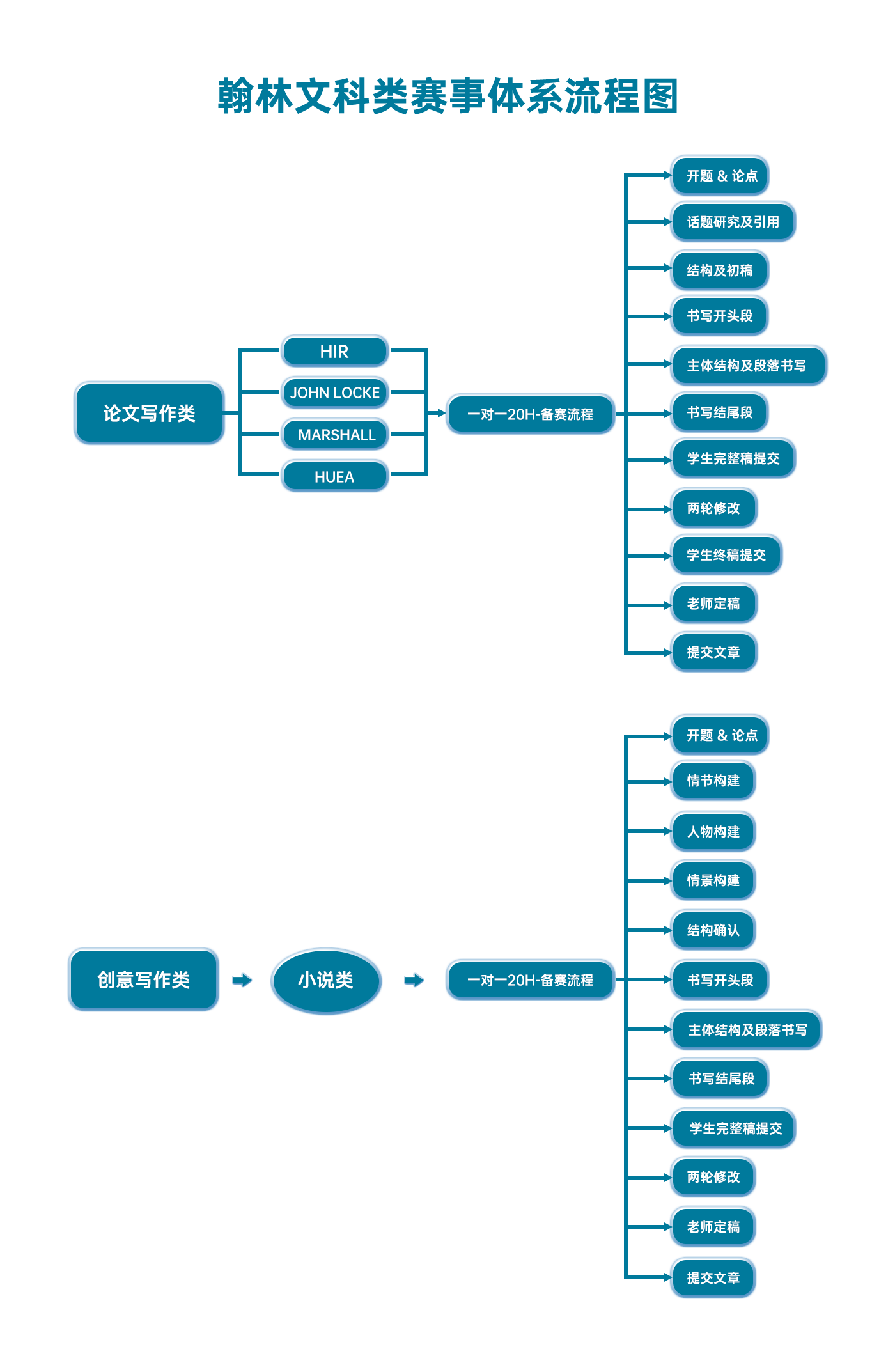

翰林文科学术活动课程体系流程图

早鸟钜惠!翰林2025暑期班课上线

最新发布

© 2025. All Rights Reserved. 沪ICP备2023009024号-1