- 翰林提供学术活动、国际课程、科研项目一站式留学背景提升服务!

- 400 888 0080

2020年John Locke论文写作竞赛经济学一等奖论文全文

约翰洛克写作学术活动(John Locke)是由位于英国牛津的独立教育组织John Locke Institute与英国牛津大学和美国普林斯顿大学等名校教授合作组织的学术项目,意在考察学生在不同学科领域内的基本知识结构,议论文的基本写作格式与技巧,独立思考能力以及清晰的逻辑和辩证分析能力。以17世纪英国著名哲学家、古典自由主义鼻祖John Locke命名,是人文社科含金量最高的国际征文比赛之一。

John Locke写作比赛提供哲学、政治、经济学、历史、心理学、宗教、法律共七个领域的内容(仅限高中组,初中组题目是额外的),喜爱文科方向的学生绝对不要错过!

2022年6月30日 晚上11:59pm(GMT)

● 高年级组:15岁~18岁

● 低年级组:15岁及以下

Q1. Is Bitcoin a blessing or a curse?

Q2. What’s wrong with the housing market? How can we fix it?

Q3. Should Amazon pay people more? What would happen if they immediately increased every worker’s salary by twenty percent?

Q4. Is Henry George’s land value tax fair, efficient, both, or neither?

What is the socially efficient level of crime?

Raphael Conte, Sir William Borlase's Grammar School, United Kingdom

Winner of the 2020 Economics Prize | 10 min read

In this essay, it is argued that the socially efficient level of crime is actually significantly above nil, despite rampant social costs, due to the necessary trade-off between prevention expenditure and costs inflicted by crimes, as well as the potential beneficial effects of crime.[1] However, it must be recognised that there is no ‘simple relationship’ between crime and social costs derived from it, although cost-benefit analysis supplemented by case studies provides an indication.[2] Firstly, there are the social costs of crime with an added opportunity cost dimension. Secondly, there are prevention costs followed by the potential social benefits. Finally, the use of fines may help to determine a socially efficient level. Here, crime refers to various acts that imply a transgression of social norms and are punishable by law, from financial crimes to homicide, although naturally “crime” can have varying definitions, within different legal systems.

In this context, ‘social efficiency’ can be characterised as taking all the consequences of crime on all economic agents into consideration.[3] Specifically, social efficiency can be defined as: marginal social costs totalling marginal social benefits (MSC=MSB) with social costs divided into preemptive prevention costs and the social costs of the crimes expenditure and costs inflicted by crimes, as well as the potential beneficial effects of crimes themselves.[4] Therefore, in order to minimise overall social costs, the marginal cost of preventing crime should equal the marginal social cost of crime (MCp=MSC). If MCp>MSC of crime, then crimes are more costly to prevent than allowing them to occur, thus contributing to a higher overall social cost. Contrastingly, if MCp<MSC, then crime could have been prevented at a lower social cost than the social cost inflicted by the crime.

However, it can be argued that the socially efficient level of crime is nil as it is ‘the primary source of inefficiency in the economy,’ effectively ‘bypassing the market.’[5] [6]Principally, external costs involved in crime can be so considerable that it should not be present at all. This includes costs attached to crime which can be divided into apprehension, conviction and punishment costs.[7] Firstly, apprehension costs can be estimated using UK police spending, which was £14,063m in 2019-20. [8]Secondly, average unit conviction costs range from £200 for commercial theft to £800,980 for homicide. [9]Thirdly, incarceration cost the taxpayer £2,753,747,261 in the UK in 2015, i.e. £32,510 per prisoner. [10]In 2018-19, the total Ministry of Justice operating expenditure was £10 billion, with an income of £1.6 billion.[11] Similar statistics in the US are even more alarming with criminal justice system expenditure in 2012 amounting to $210 billion.[12] Such sums exemplify the huge social costs of crime, suggesting that the optimum level is close to nil, if not absolute zero.

Additionally, there are considerable social costs as consequences of crime, such as the lost output of crime victims. For example, in the UK, the average cost of lost productivity for violent crime victims is £2,060 (5 hours off work and 36 reduced productivity hours).[13] The same rationale can be used to estimate the social costs of crime regarding healthcare costs. For the same crime, average unit costs of healthcare amount to £920.[14] Moreover, there are also large anticipatory and reactionary social costs, notably defensive precautions taken by potential victims. This includes a range of measures such as insurance, locks, doors, private CCTV and alarms, with UK cost estimates ranging from £3bn to £4bn to around £25bn.’[15] This allocation of resources to hinder crime naturally inflicts significant monetary and psychological costs to society, although it does provide employment and other economic benefits. Similarly, resources used to commit a crime also represent costs to society.[16] [17]Here, an opportunity cost dimension must be added to fully capture the argument.[18] Principally, the criminals’ human and physical capital could have been utilised to contribute to the productive potential of the economy, creating potential social gains instead of inflicting high social costs through crime. This opportunity cost also includes the resources expended by potential victims to protect themselves from crime. The next best alternative may have been expenditure on goods and services to improve real living standards.

However, it can also be argued that the socially efficient level of crime is relatively high because resources allocated towards prevention can generate an even greater burden on society than if some crimes were allowed to occur (MCp<MSC). This is corroborated by Friedman stating that ‘theft is inefficient, but spending $100 to prevent a $10 theft is more inefficient.’[19] The following analysis can be divided into the high monetary and non-monetary costs of prevention.

On a monetary level, such high costs would take the form of expenditure on human and physical resources such as enhanced police presence and surveillance. Although this creates employment, an opportunity cost is still presented. In order to estimate the expenditure required to bring crime levels close to 0, the example of Singapore can be used where high penalties are coupled with high policing expenditure of over $200 US per capita[20] to achieve a relatively low crime rate of 617 per 100,000 with an intentional homicide rate of 0.7 per 100,000.[21] [22]This also implies that innumerable resources would be required to achieve a point where crime was virtually nil, inflicting even greater social costs through taxation than the crimes themselves.

Non-monetary costs of prevention also suggest that the socially efficient level of crime is well above nil. These social costs focus on the infringements of citizens’ rights and liberties, such as freedom of assembly and movement, which would undoubtedly be restricted by a police state seeking extremely low levels of crime. A relevant example for this is the former GDR where the Secret Police crushed crime and dissent through ‘increased social control, draconian state sanctions and reduced opportunity structures.’[23] However, this inevitably led to spiralling long-term social costs with recent articles stating that ‘memories of the police state continue to exact a profound psychological toll,’ even 30 years after German reunification.[24] As a consequence of the actions of the Stasi, psychologists have diagnosed various conditions, including post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety and depression.[25] Overall, this case study demonstrates how efforts to reduce crime to very low levels tend to lead to far greater social costs than those actually created by crimes themselves. This example shows the lasting harm of such measures. Even if a more social-liberal rather than authoritarian approach was taken, as in Scandinavian countries, whereby the incentive to commit crime is reduced through redistributive measures, costs would remain high and crime would probably persist. Even today, economists argue that in the USA, ‘spending less on policing would increase social welfare.[26]

However, the idea that prevention is better than cure can also be applied with regard to crime. Although it is very difficult to calculate the social benefit stemming from preventative measures, a study of CCTV (closed-circuit television) suggests that the trade-off between infringement on civil rights and liberties and reducing crime is not as great as commonly perceived. Firstly, it is accepted that ‘CCTV can, when properly implemented and monitored, be effective at reducing crime.’[27] However, Roman and Farrell also argue that ‘there is evidence that CCTV can be introduced without infringing upon people's freedoms.’[28] Similarly, the argument regarding the infringement on civil liberties is weakened by the fact that it is arguing ‘for a right to anonymously commit crime.’[29] Therefore, as technology develops, it can be argued that the trade-off between prevention and social costs created is becoming less applicable, suggesting that the socially efficient level will decrease in the long-term.

Secondly, it can be claimed that the socially efficient level of crime in some circumstances is perhaps surprisingly high, due to the potential social benefits. This is particularly significant in relation to redistributive crimes such as theft and fraud which are effectively transfer payments. From a utilitarian perspective, if some resources are reallocated from wealthier agents to poorer agents, then total utility for the overall population increases. This is explained by the law of diminishing marginal utility which states that less affluent agents have higher levels of marginal utility, i.e. an increase in their resources will dramatically improve living standards. If crime can have this effect, then this may be able to improve development outcomes. From a macroeconomic perspective, the transfer will increase consumption, a key component of aggregate demand (AD=C+I+G+(X-M)) (AD-AD1) due to poorer individuals’ higher marginal propensity to consume which could, in turn, lead to an expansion of GDP (Y-Y1). This suggests that a certain type and level of crime can lead to economic benefits. However, the net improvement is likely to be marginal and will reduce long-term consumption trends. From a microeconomic perspective, if a poor thief were more likely to purchase merit goods and the wealthy were more likely to buy demerit goods, then crime would be contributing to correcting market failures caused by negative externalities.

2022年John Locke论文学术活动已经放题啦!

对其他学科领域感兴趣的同学

可扫码添加微信咨询

免费领取历年相关获奖论文学习

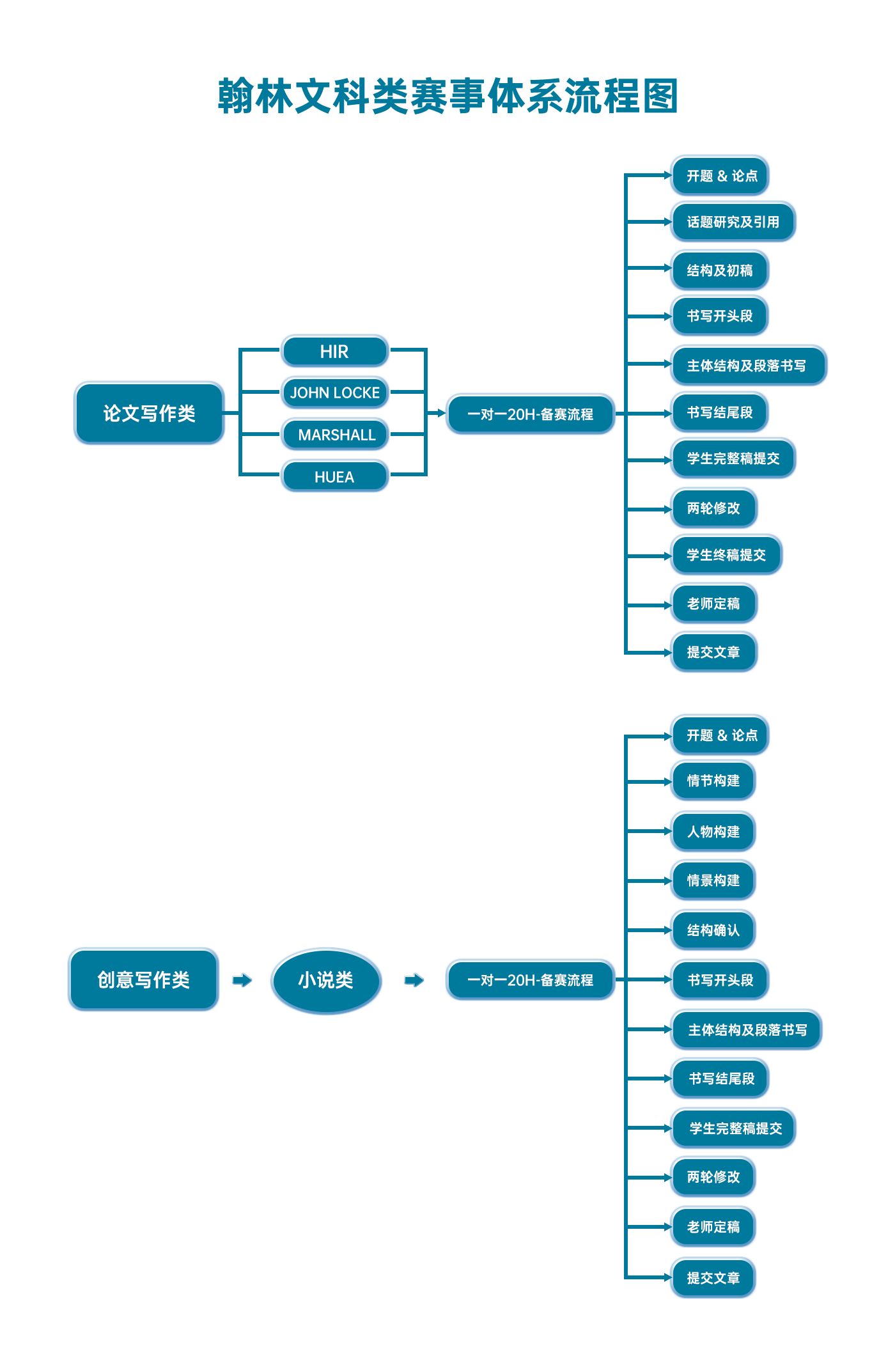

翰林文科学术活动课程体系流程图

最新发布

© 2026. All Rights Reserved. 沪ICP备2023009024号-1