- 翰林提供学术活动、国际课程、科研项目一站式留学背景提升服务!

- 400 888 0080

2020年john locke论文竞赛法律专业First Prize全文

2020年john locke论文学术活动法律专业First Prize全文公布,今年的学术活动即将开始,回顾过往的论文对于冲刺备战是有帮助的,一起跟着小编来看看john locke论文学术活动法律专业一等奖的全文是什么内容。

Does a law that prohibits the selling of sex protects or infringe women's rights?

Cai Sirui, Raffles Institution, Singapore

Winner of the 2020 Law Prize | 8 min read

“Slavery still exists, but now it applies onto to women and its name in prostitution”, wrote Victor Hugo in Les Misérables. Hugo’s portrayal of Fantine under the archetype of a fallen woman forced into prostitution by the most unfortunate of circumstances cannot be more jarringly different from the empowerment-seeking sex workers seen today, highlighting the wide-ranging nuances associated with commercial sex and its implications on the women in the trade. Yet, would Hugo have supported a law prohibiting the selling of sex for the protection of Fantine’s rights?

As can be seen from the drastic variation in related legal framework across countries, the debate surrounding the regulation of commercial sex is one that is inexplicably linked to morality, human rights and gender roles - and one with no easy answer at that. Before delving into my arguments, I will clarify some key terms and set the scope of discussion: “selling of sex” will be defined as the provision of sexual services in exchange for money or goods, an action in which the prostitute is the doer. A law that prohibits the selling of sex would thus be a law that criminalises and punishes the party providing the sexual services (on top of other parties involved, in most cases), which is most aligned to the prohibitionist model in amongst the four broad models widely referenced by recent literature (Chuang, 2010). While the selling of sex is most definitely not exclusively carried out by women, this essay will limit its discussion as such, given its focus on the implications on women’s rights as well as the relative rarity of male sex work (Brussa, 2004). With these in mind, I argue that a law that prohibits the selling of sex infringes - rather than protects - women’s rights, on the grounds of the validity of the empowerment narrative as well as the limitations of the law in enforcing the rights of vulnerable women in practice.

A key argument proffered by those who believe that prohibiting the selling of sex would protect women’s rights is that prostitution is a violation of human rights in itself, it being a form of oppression against women that is inherently coercive. This is clearly spelt out in the United Nations Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Persons and the Exploitation of the Prostitution of Others (1950), which states in its preamble that “Prostitution ... (is) incompatible with the dignity and worth of the human person”. It naturally follows that such blatant violation of the most fundamental of rights should not be condoned by the law.

In a similar vein, a further argument in favour of a law prohibiting the selling of sex is that prostitution is the product of structural and institutionalised male dominance, such that the lack of prohibitive legislation would further reinforce and legitimise the patriarchy at the expense of women’s rights and their standing in society. Against the context of long standing patriarchism and the systemic oppression of women (Dobash and Dobash, 1981), sexual commerce perpetuates women’s subordination to men through providing a patriarchal right of access to women’s bodies (Farley, 2005). Women are seen as a mere means to an end, their bodies a mere commodity at the disposal of men seeking sexual satisfaction, only worth the money they receive in exchange for their services. In the absence of a law prohibiting all aspects of the sex trade, such oppression of women is not only allowed to continue, but also institutionally legitimised. This clearly compromises the status of women, infringing their rights to own their bodies and to be counted as equals to the other sex.

While I recognise the validity of the argument that prostitution is harmful to women who had limited agency in entering the trade, a more comprehensive picture would encapsulate a dual reality of empowerment and exploitation (Sagade and Forster, 2019). In the case of the former, prohibition encroaches on the sex worker’s autonomy to free choice of work; for the latter, a law prohibiting the selling of sex is unlikely to be efffective in protecting vulnerable women from the harms of prostitution; it might even work to the opposite effect.

Both of the above arguments in favour of prohibition hinge on the premise that the selling of sex can never be voluntary. They posit that sex workers are the victims of rape and exploitation who lack agency and therefore have no genuine consensual capacity (Tiefenbrun, 2002 and Sullivan, 2007). However, recent developments in the sex positivism movement have surfaced the voices of women who make the rational and voluntary choice to sell sex for an income, to whom prostitution should be seen as legitimate work. At the 2015 Amnesty International Conference, Meg Munoz, a former sex worker, spoke up to advocate for the legitimisation of sex work, stating that escorting served her well, as a source of income and even stability. Similar narratives can be found on the blog ‘Tits and Sass’, on which sex workers contribute entries that seek to celebrate sex worker culture and destigmatise prostitution as immoral and degrading.

One might point out that such activists are a minority who are educated and make hundreds of dollars per hour (Bazelon, 2016), but they do represent authentic and legitimate views of a group of sex workers. For these women, the criminalisation of prostitution is an overly paternalistic move which infringes rights to free choice of work and overall self-determination. Article 23(1) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) states that all should have the right ‘to work, to free choice of employment, to just and favourable conditions of work and to protection against unemployment’. In dictating to women that working in prostitution is inherently ‘wrong’, the state is denying them the ability to exercise agency through the negotiation of their sexual autonomy (Sagade and Foster, 2018), drawing the line on what sexual acts are intimate when the decision should have been the individual’s to make, thereby clamping down on their rights to self-determination.

Certainly, this is not to discount the fact that for the majority of female sex workers, selling sex, if a voluntary choice at all, is made as a result of limited alternatives and disadvantaged circumstances. For this group of women, exploitation is an unfortunate reality, seeking “empowerment” in sex work a far flung fantasy. For example, in India, women and children are trafficked for commercial exploitation either by deception or coercion, and some are sold by family members or family friends into sex work, typically in the context of rural poverty, food insecurity and large families (Patel, 2013). Even when direct coercion is not involved, it is common for women to enter prostitution because they are faced with economic insecurity and limited alternatives, choosing this line of work as the “lesser evil”.

In such cases, the harms brought about by prostitution are real and pressing, and the rights of women are inevitably compromised by them being in the sex trade. This, however, does not mean that a law prohibiting the selling of sex will serve to protect their rights; in fact, it is quite the contrary.

First, the argument that prohibiting the selling of sex protects the rights of vulnerable women breaks down when examining how such a law would function in practice. There is little reason to believe that such legislation would be effective in eradicating prostitution; it has long been the case that as long as demand for commercial sex exists, the sex trade will remain, bringing its activities underground and carrying them out illegally. For example, in China, Japan and South Korea - all of which adopt a prohibitionist model - prostitution remains rampant, the sex trade even contributing copious amounts of revenue to the countries’ economies (US Department of State, 2009 and Thompson, 2016).

Furthermore, to charge and punish a woman selling sex can make it more difficult for her to leave the sex trade, further promoting prostitution instead of preventing it (Mullin, 2020). When burdened with a fine, women tend to continue to prostitute themselves in order to pay off the fine. When charged with an offence, a criminal record jeopardises future employability, which forces women to remain in the industry. It is thus clear that merely having a law that prohibits the selling of sex without addressing the root causes of prostitution is largely ineffective in removing the existence of such exchanges; in actual practice, such a law fails to protect women from the harms associated with selling sex, thereby invalidating the above claims that prohibition protects women’s rights.

Not only does a law prohibiting the selling of sex stop short of curbing prostitution and the harms that come with it, it is also likely to further exacerbate the vulnerability of women in the sex trade. When the status of women selling sex is unlawful, they are marginalised, being viewed as criminals (Vance, 2011) and become susceptible to sexual abuse and violence from clients, brothel owners and the police. In Cambodia, for example, law enforcers have used the law on the Suppression of Human Trafficking and Sexual Exploitation to exploit and abuse sex workers, whose statuses are unlawful due to the prohibitionist legislation. In some cases, sex workers have been forced to pay bribes to avoid arrest or have been raped by officers after being detained (Mullin, 2020).

For women to whom simply exiting the trade is not a viable option, a prohibitive law also means that they would be denied protection by the law in areas such as their safety, health and children, infringing on these basic rights. This leaves them worse off than they would have been otherwise; not only do they continue to be exploited sexually (now without the protection of labour law), they are also subject to penalisation on all fronts. For instance, their children could be expelled from school, and they could find themselves unable to find lawful accommodation. Stigma, poverty, and exclusion from legal social services would also increase their vulnerability to HIV infection. Without tackling the root of the problem - the conditions under which women resort to prostitution in the first place - assigning them an unlawful status brings more harm than good where their rights are concerned.

Even if the law were an effective deterrent such that women would be incentivised to leave the trade as a result, it does not necessarily follow that they would then have fully escaped the wrath of sexual exploitation and rights would be better protected henceforth. Given the fact that vulnerable women are already in disadvantaged positions with limited choices for work, pushing them out of sex work might lead to even more detrimental circumstances. For instance, Indian sex workers cited in interviews that their former occupations - typically domestic service, construction or factory work - were often exploitative and coercive, including expectations of sexual exchanges for work assignments (Sahni & Shankar, 2013). Should they return to these in place of sex work, they would still be exploited sexually, but this time without remuneration, legal protection or control over their sexual exchanges. In this case, their human rights and standing in society compared to men is further jeopardised, which shows that even in the unlikely event that the legal prohibition of the selling of sex succeeds in reducing prostitution, systemic threats to women’s rights remain.

To conclude, in acknowledging the legitimacy of both the empowerment and exploitation narratives, it is clear that at best, legislation against the selling of sex fails to protect women’s rights; at worst, it further infringes them. In order to protect the rights of the vulnerable women in the sex trade, an abolitionist framework - in which buyers and other participants in the sex trade are criminalised but not the women themselves - might be a better alternative to full prohibition. This must also be accompanied by efforts outside the legal sphere to tackle the problem in more fundamental ways, such as lifting women out of socially and economically vulnerable positions so that they do not have to resort to selling sex for money in the first place.

Bibliography

Bazelon, E. (2016, May 5). Should Prostitution Be a Crime? Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/08/magazine/should-prostitution-be-a-crime.html

Brussa L. (2004). European network for AIDS & STD prevention among migrant prostitutes. Final report No. 6, June 2002-June 2004. Amsterdam: TAMPEP International Foundation.

Chuang, J. (2010). Rescuing trafficking from ideological capture: Prostitution reform and anti-trafficking law and policy. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 158(6), 1655–1666.

Dobash, R. E., & Dobash, R. (1981). Violence Against Wives: A Case Against the Patriarchy. Contemporary Sociology, 10(3), 413. doi: 10.2307/2067357

Farley, M. (2005). Prostitution Harms Women Even if Indoors. Violence Against Women, 11(7), 950–964. doi: 10.1177/1077801205276987

Mullin, E. (2020, January 20). How Different Legislative Approaches Impact Sex-Workers. Retrieved from https://theowp.org/reports/how-different-legislative-approaches-impact-sex-workers/

Patel, R. (2013). The trafficking of women in India: A four-dimensional analysis. Georgetown Journal of Gender and the Law, 14(1), 159–188.

Sagade, J., & Forster, C. (2018). Recognising the Human Rights of Female Sex Workers in India: Moving from Prohibition to Decriminalisation and a Pro-work Model. Indian Journal of Gender

Studies, 25(1), 26–46. doi: 10.1177/0971521517738450

Sahni, R., & Shankar, K. (2013). Sex work and its linkages with informal labour markets in India: Findings from the first pan-India survey of female sex workers (IDS Working Paper No. 416).

Retrieved from http://www.ids. ac.uk/files/dmfile/Wp416.pdf

Sullivan, B. (2007). Rape, prostitution and consent. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 40(2), 127–142.

Thompson, N. (28 February 2016). Is Japan Having Sex?. GlobalVoices. Tiefenbrun, S. (2002). The Saga of Susannah - A U.S. Remedy for Sex Trafficking in Women: The Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000. Utah Law Review, 107–175. Retrieved from https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/utahlr2002&div=10&id=&page=

United Nations (1950). Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Persons and the Exploitation of the Prostitution of Others. Retrieved from https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=VII-11-a&ch apter=7

United Nations (1948). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/

United States Department of State (25 February 2009). 2008 Human Rights Report: China (includes Tibet, Hong Kong, and Macau). Section 5: Discrimination, Societal Abuse, and Trafficking in Persons.

Vance, C. (2011). States of Contradiction: Twelve Ways to Do Nothing about Trafficking While Pretending To. Social Research, 78(3), 933-948. Retrieved June 1, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/23347022

扫码【免费获取】全部获奖作品,2022john locke论文学术活动即将开始,提前备战,名师辅导,做到心中有数!

专业人,做专业事!

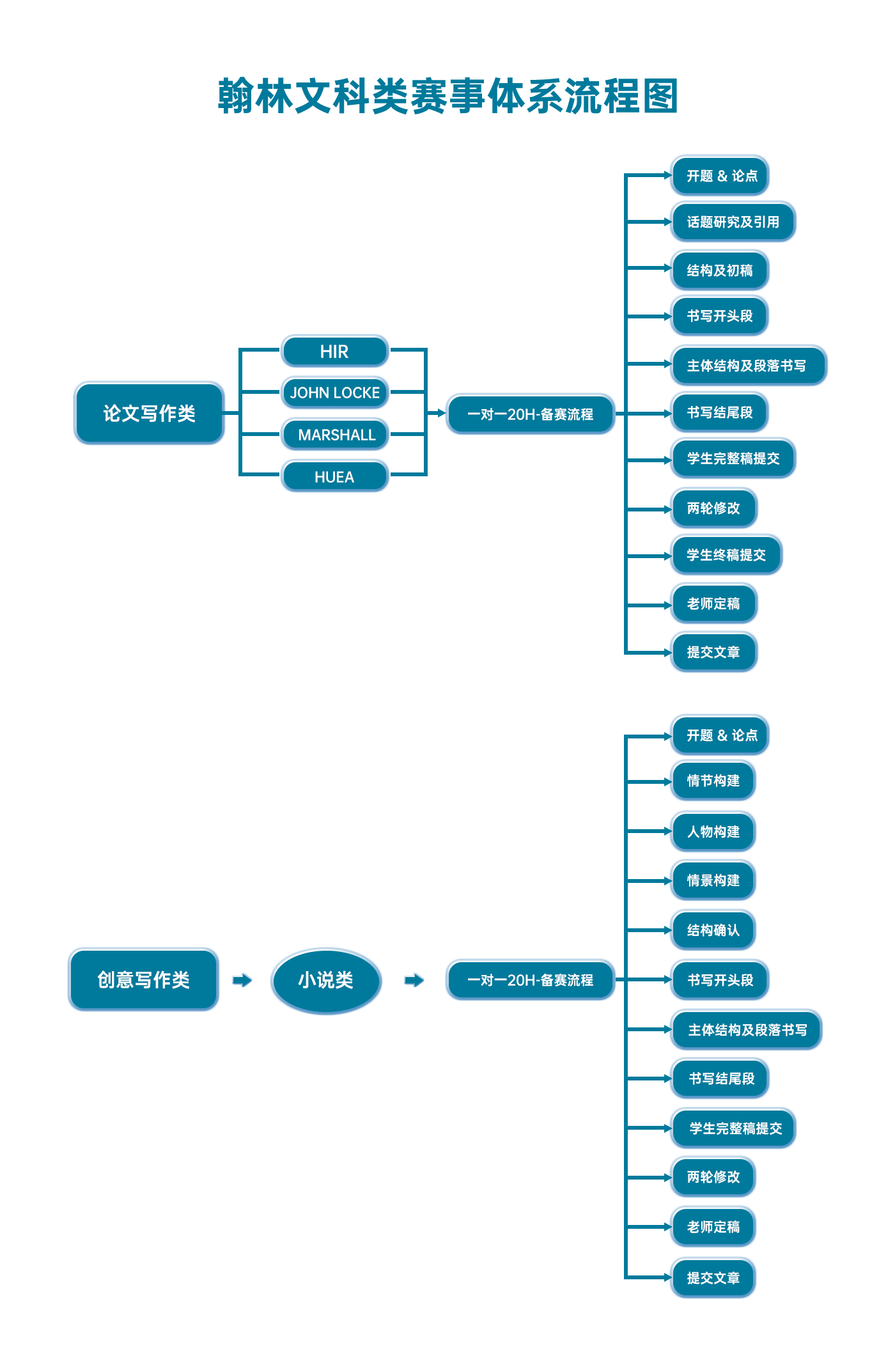

翰林文科学术活动课程体系流程图

早鸟钜惠!翰林2025暑期班课上线

最新发布

© 2025. All Rights Reserved. 沪ICP备2023009024号-1