北美热门的创意写作大赛Scholastic Art & Writing终于一改往年的传统提交,上了新系统,全面实现线上支付!

咱们可以远离邮寄支票,打印签字表的日子了!

但是不出意外的话

就要有意外了

由于这次启用了新系统

出现了各种提交系统崩溃

以至于不同地区的截止日期一延再延

......

01 / 突发状况 /

官方系统出现问题,注意提交可能延迟!

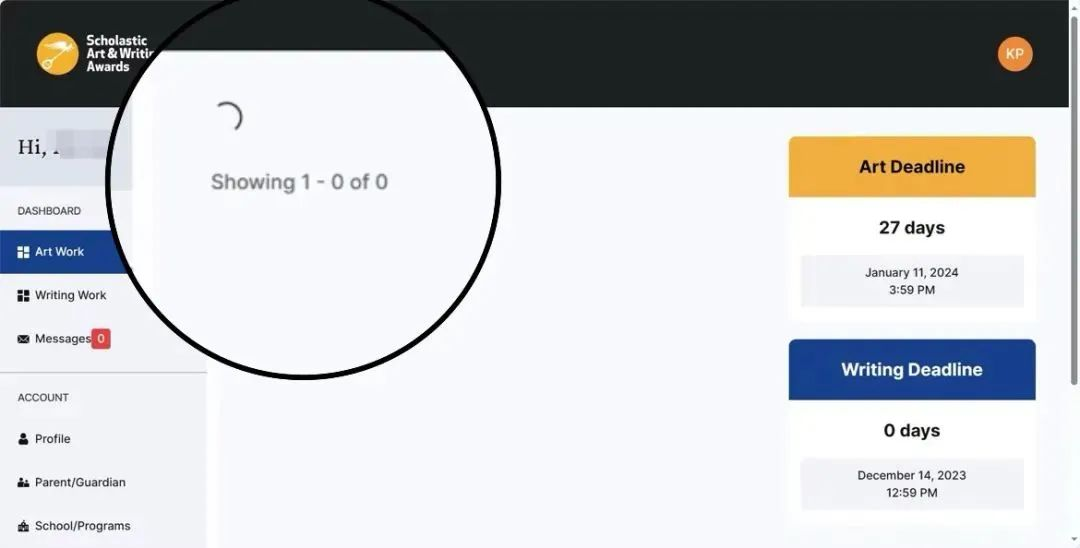

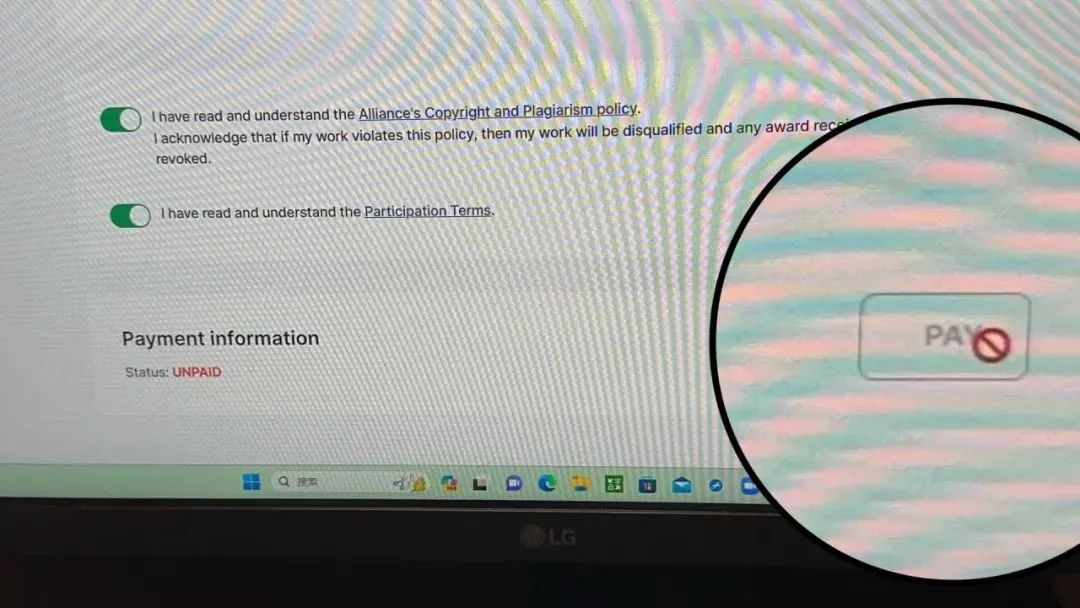

继今年官方更新系统后,频频出现突发问题,多地提交出现网页错误,如无法提交、无法付款、上传失败等状况。

无法提交

无法提交

无法付款

无法付款

针对这次的系统问题

官方给出了提交截止日期延迟的消息

(具体根据官网最新信息为准)

(具体根据官网最新信息为准)

据官网消息,新系统存在技术问题。

▶目前提交截止日期延至2024.2.29(具体因地区而异)

对于截止日期原本在2024.1.15-2024.2.29的学生,在2024年1月1日前,需要暂停访问网站,暂时先不要提交,至24年1月起关注官网信息再进行相关操作。

面对这一情况

我们有几个应对措施建议给到大家👇

👉 尽早上传

已经准备好提交稿的学生建议尽早上传,有问题可以提前和官方联系。

👉 有备无患

已经明确延期的同学可以趁此机会考虑多投一投作品,也可联系我们,请导师帮助大家梳理、优化可投作品~

👉 紧急优化

危机即转机,面对突发状况,更应抓住机会,做好最后优化!

时间紧急!把握机会!我们有丰富经验的导师团队协助你,并对你的论文进行修改指导,帮助你在短时间内提升作品质量!

如果对【Scholastic Art & Writing】感兴趣,欢迎扫码咨询!

02 Scholastic Art & Writing Awards

学生优秀案例分析

奖项:银奖

类别:短篇小说

👉 备赛评析

1、这位同学成功地讲述了一个引人入胜的故事。故事使用了一些高级的手法,尤其对于人物和画作的刻画,使故事的核心思想更凸显。

2、作品没有获得金奖,原因可能在与写作风格。这个故事的想法很有创意,但散文式的叙事风格让作品想要表达的意义不够稳固。

H同学

奖项:荣誉奖

类别:科幻小说

👉 备赛评析

H同学在开始创作时仅仅是有一个想写科幻小说的想法:通过玩具的视角去构建一个世界,隐喻社会中的不公正。K导师通过设定主角形象、与其他故事人物的关系、发生了哪些事等一步步引导H同学完成了这部小说。

小说讲述了一个人某天醒来变成了不倒翁玩具,当他和社会上其他被变成物品的人交朋友时,他发现了不公正。最终H同学获得荣誉奖。

W同学

类别:微小说

👉 备赛评析

W同学的创作思路与H同学截然不同,在与她刚接触时,已经有一份完整的草稿,讲述的是关于一个女孩鬼魂的故事——在她被谋杀后,她只能眼睁睁地看着她的社区里的人继续他们的生活。

K导师引导W同学去思考这个故事的意义,将其中的一些细节背后的深意进行提炼突出,使作品得到质的提升。

03 赛事特色

Scholastic究竟有何特别之处?

高含金量

根据官方统计,每年美国各地的学生提交超30万件原创作品,仅仅2000多名学生获得荣誉奖项,获奖率不足0.6%,其的难度和价值是不言而喻的,同时也意味着,这将是申请名校和奖学金的加分项!

多维能力培养

美国大学在选择学生时选取的审核标准是“综合全面评审”(Holistic Review)。这意味着标化成绩并不是录取的唯一条件,高校们更关注学生的综合能力。

就综合能力而言,其中最重要的莫过于学术能力。而Scholastic竞赛对学生学术能力的培养不仅是多样化的,更是专业化的,尤其是学术写作相关的能力。

04 Scholastic Art & Writing Awards

赛事详情

关于学乐艺术与写作奖

Scholastic美国学术艺术与写作奖由美国青年艺术家、作家联盟于1923年设立,是全美国历史最悠久、最负盛名的文学艺术竞赛。赛事每年与美国100多个诗句艺术和文学艺术组织合作,旨在发现最有创意与灵感的青少年艺术与文学作品。

优秀获奖者不仅可以参加全美巡回展览,更有机会获得现金奖励和高达10,000美金的奖学金。

写作类别

大赛分类诸多,其中包括11种写作类别,在全美范围内评选出最具创意、技巧和个人特色的佳作。

1.Critical Essay评论文章

2.Dramatic Script剧本

3.Flash Fiction微小说

4.Humor喜剧

5.Journalism新闻稿

6.Novel Writing小说

7.Personal Essay&Memoir个人陈述&自传

8.Poetry诗歌

9.Science Fiction&Fantasy科幻小说

10.Short Story短篇小说

11.Writing Portfolio写作作品集

参赛资格

7-12年级13岁以上,对文学、艺术创作感兴趣的美国或加拿大地区就读的学生们均可参加。

提交时间

2024年2月29日比赛截止(具体根据官网最新信息为准),注意比赛截止日期因地区而异,考虑到今年的系统问题,建议同学们尽早准备!避免错过机会哦!

05 Scholastic Art & Writing Awards

2023亚裔金奖作品赏析

Critical Essay

作者:Zoe Yu

“Unfortunately, students’ brains are not fully developed until they are 25 or 26 years old.”

I’m frantically combing through Facebook before the bell rings for class. My op-ed on Covid in schools had gone live that week, and it had become a sort of ritual to check the response on social media in between club meetings, quizzes, and homework. I had written about a highly politicized topic, so I was braced for scathing pushback—but scrolling through the thousands of comments, I realized that almost no one was discussing what I had written about, and almost everyone was discussing my age.

Under the article, someone had suggested that I get a summer job in the real world instead of typing up fake news, throwing in a “Don’t you have a math test to study for?” Another told me sympathetically that my young, impressionable mind had been brainwashed by my parents, peppering their advice with “sweetheart” and “child.” Some comments even questioned if I had written the article myself—“Middle-aged hands typed this,” “So what kid made money for this interview?”—and a far-right media organization called me a propagandist with a teenage persona. When I tapped into the comments section of someone who had shared the article with an angry emoticon, I saw that her friend had chimed in, too: “My sis-in-law owns a dance studio & says kids’ brains have definitely been affected . . . sad & scary as hell! . . . muzzled = lack of oxygen to the brain . . .”

As I saw my writing sabotaged by my age in real time, I wondered how many stories had gone untold because of responses like these. How many young writers had written a piece that was important to them, only to be met with scorn and condescension? How many valuable stories had been lost in the shuffle of “You’re just a kid”? And how many more would be?

When we aren’t being told that we lack the life experience and wisdom to write, we’re being dismissed as too childish, ignorant, or naive to know what’s going on, too influenced by outside forces to be able to think for ourselves. What on the surface may read like the casually cruel comments so often thrown around on the internet are symptomatic of a deeper issue: Young writers aren’t taken seriously. Our writing is routinely discounted—not because of the message, or the sources, or anything regarding the actual content of a piece—but simply because of our age. This is despite young writers’ covering topics that have a direct impact on us: At the same time that we’re growing up, navigating adolescence, and figuring out our place in the world, we’re also writing about it.

Who is best suited to write about the student debt crisis if not a low-income teen struggling to pay for his education? Whose story is it to tell of being five months pregnant at prom if not a teen mother’s? Who should be tasked with profiling the stories of victims of the school gun violence epidemic if not high school students who endure active-shooter drills every school year? The act of listening to young people and giving us the space to write doesn’t just let us vocalize our perspectives and validate our opinions; it also brings an authentic portrayal of the unique issues that we’re facing as we face them. Whether we have a curfew or not, and even if our history project is due on Monday, we should be able to write without being written off.

From reporting on the coronavirus to dissecting culture and identity, we’re doing serious work. It’s exactly what we need: responsible coverage of what’s happening right now from the people living through it. We can’t brush these stories off, even if—especially if—they’re told by teenagers.

Yet we are. In an industry where online harassment—especially of women— is expected, biting insults aren’t uncommon, but for many young writers, they hit hard. “A constant barrage of ageist comments can be really harmful,” Miceala Morano, a high school senior and an award-winning writer and slam poet, tells me. “I’ve had friends who have stopped writing completely because a comment was so rude that it destroyed their sense of confidence in themselves and their work.” Opening up my Twitter DMs, with readers questioning my credibility and declaring I was more fit to watch “Dora the Explorer,” I felt for young writers who face unnecessarily harsh critics. We can come across as self-assured, but in a time when many of us are just starting to summon up the courage to write publicly, it takes only one seemingly offhand remark to undermine days of writing, researching, and reporting.

Ageism also extends past patronizing comments into tangible consequences. In Kentucky, high school journalists were shut out of a 2019 roundtable discussion on, ironically, education. Unable to cover the event, they wrote an editorial instead, asking, “How odd is it that even though future generations of students’ experiences could be based on what was discussed, that we, actual students, were turned away?” It’s demoralizing, and all too familiar, to see seasoned writers and professional journalists entering an event as student journalists are held back, watching from the sidelines when we should be in the thick of the action. We’re expected to prove ourselves without ever being given the chance to do so.

Rainier Harris, a freshman at Columbia University who wrote for The New York Times in his senior year of high school, knows this frustration all too well: He says he’s been pushed aside by editors who deem young journalists too inexperienced to cover a story, and has been offered less than what he feels is deserved for the quality of his work. Somewhat contradictorily, it seems editors expect experience without ever allowing young writers to build it—which is the exact opposite mentality of what’s needed to allow young writers to bring their stories into the fray. “Young people have amazing stories to share, and we [should] be telling them,” Harris says.

Adding the word “teen” before “writer” or “student” before “journalist” shouldn’t condemn a piece of writing to be perceived as amateur or inane, and this attitude about age dictating worthiness is a disservice to the billions of young people across the globe. As we create important, meaningful work, our opinions and voices should be treated with respect, regardless of how old we might be. “Young writer” isn’t an oxymoron.

Short Story

作者:Nora Sun

She bore the journey alone. The jade waters which sloshed on a wooden deck beneath the swollen moon cast a lasting grayness on her skin. The torrential rain that tossed the ship’s ragged carcass about opened sores in her body that never truly closed. The briny scent of sea clung to her long after she set foot on land, and the white men regarded it like an exotic perfume, like she was one of their Western fish-tailed women. Day by day, she inched forward towards the other coast, a fragile singular star traversing the velvety sea in a wind-blown arc.

After twenty days hidden in the storage ship, a pale figure clutching a shimmering brocade emerged in the harbor. In the Lunar calendar, it was an inauspicious date for big changes. In the American calendar, it was a Tuesday in 1988. She stood on that shore, her clothes dirty and hair ragged, regarding the American world around her. No gold bubbled from the ground. No fish fell from the sky. The sun was neither brighter nor warmer than it was in Hong Kong. But it did not matter. Her little island had long been swallowed by the sunset. This was her homeland now.

—

Sima Buming was the name she had been given, but the Needle Mistress was the name she earned. Her practice sat in a strip mall at the center of Chinatown, the vermillion heart of a sprawling city that wore a skirt of gray skyscrapers. The entrance was marked by a plain plastic sign in the window that read “Pain Relief Acupuncture PLLC 针灸止痛” and printed a few prices for different services in Chinese and English. She was neighbors with a hair salon and a Chinese grocery.

The interior was as humble as the exterior. The 120 square-foot room contained a soft-bellied black-leather treatment table for the patient, a rattling metal table to hold supplies, and a faded second-hand couch where two waiting customers could sit. Most conspicuously, at the back of the office behind the medical table, there hung a beautiful golden brocade with a delicately embroidered Qilin leaping across its surface. Each scale of the Qilin was woven with glistening silver and blue thread, and its claws were dyed a shade of black that swallowed all light.

During the first few months when she hardly had any customers, she considered selling this priceless brocade many times. In the end, she could not bring herself to. The Qilin brocade was passed down from generation to generation, a gift at sixteen for mastering the Sima family art of acupuncture. It hung like a haunting from her past, reminding her of her duty to carry on and pass down her legacy. No matter how hungry she was, she would not sell her family.

Fortunately, her prices were cheap, and her skill was good. Eventually, a few customers trickled in, speaking only Chinese and complaining of back pain. One by one, they lay down on the treatment table, faces marked by skepticism.

She knew the flow of qi through the human body better than any other living soul. The jīngmài (經脈) and luòmài (絡脈) were stationed like gates to a body’s vital force, which overflowed along the twenty major pathways within the body. She had memorized the standard and extraordinary meridians when she was a child of seven years, running barefoot in her mother’s clinic.

One by one, she diagnosed the source of their pain. She selected a configuration of the 950 acupuncture points passed down in the tablets of the Sima family and inserted the delicate needles into them, relieving tension and blockages of qi flow. Delighted by the miraculous effects of what they had believed to be a pseudoscience, her customers went to tell their friends, and soon, stories of the Needle Mistress working miracles ran like wild geese among the hottest gossip tables in Chinatown.

—

It was the Needle Mistress’ gentleness that forged her into a heroine. She was new to Chinatown with a mysterious background. She was eighteen but with no signs of youth on her face, and her strangely ageless appearance had its charm. Her skin had cooked into a leathery brown in the California sun. She was fluent in pǔtōnghuà (普通话) and guǎngdōnghuà (广东话). Soft wrinkles piled up on her forehead when she concentrated. She played music of the patient’s choice from the record player that an especially wealthy customer gifted her after she relieved her of her joint pain. She was well-read and told fascinating stories to customers afraid of needles. For those with chronic pain, her soapy touch became a second home.

The Mistress saved most of her earnings and used them to slowly upgrade her clinic over the next decade. When the hair salon next door went bankrupt, she bought it, adding another 2000 square feet to her office. She purchased handsome wood and leather furniture and magazines for waiting clients to enjoy. She hired a college student to work at the front desk keeping track of patients and payments. Besides the brocade, American paintings whose style she had grown to appreciate hung on the wall in the treatment room.

On a good day, which came more and more often, she worked twelve hours and saw half a dozen customers an hour. The thin needles danced as though possessed by witchcraft at her fingertips. She began to cure cases that professional physicians and expensive medications could not. She even began to experience a slight gratification at her job, watching a decade-long ache diminish and flicker out between her fingers, accepting the repeated thanks of the client. There was meaning and pride to be found in her work. She had finally become someone in this foreign land that was no longer foreign to her.

—

Soon, the Needle Mistress’ reputation spread beyond the borders of Chinatown. Westerners from across the city also wanted to see her. She was proud—the West had traditionally upturned its nose towards the art of acupuncture if they knew what it was, but now they needed it to resolve their pain.

It was because of this that she decided to cut her hair short.

In her mother’s culture, the body was a gift from the parents—those who hurt the skin, bones, nails, and hair cooked in their mothers’ wombs were sinful and unfilial. In her family, hair was always well-maintained at the same waist length with regular small trims. But there was no such idea in this country. Altering the body was fashion. Even women from the most traditional Chinese families in Chinatown sometimes wore short hairstyles. Hair was merely a symbol of filial piety; cutting it in a trendy style would increase her appeal to Western customers, she reasoned with herself, thus growing the acupuncture business, and fulfilling her true duty to her parents.

With her hair swishing by her ears, her shoulders felt much lighter.

—

She made her first true friend in this country: a white woman from uptown named Megan. Megan was a slight, flaxen-headed housewife with a smattering of orange freckles about her nose.

In the harsh world of business, this friendship kept her warm through early winter mornings and cold meals. When summer storms loomed, Megan helped her board up windows. If there were business forms she did not know how to fill, Megan used her accounting background to explain them. They spoke of travel and escape, books they enjoyed, and the meals they cooked. Megan introduced to her what it was like to start a family. Megan’s husband and children sat in the lobby as she saw to Megan’s back pain.

She began to consider it because of Megan—starting a family. Her business was big enough. It was time to pass it down.

She heard the rumors half a year too late, the distaste that the Needle Mistress had turned her back on Chinatown and was kowtowing at the feet of the wealthy Americans. The ladies from the teahouse glared at her as she passed their window. Her favorite noodle stall spilled the soup, scalding her hands and pretending it was an accident, leaving her unable to work for a week. A traitor received no sympathy. Loyal Chinese customers who had visited her for years stopped showing, so she peddled some of the furniture and decor. Without the comfortable American couches, her uptown customers quickly left too. Megan moved away a few months later. Decades of the Mistress’s kingdom evaporated with her.

—

Perhaps the date she cut her hair was inauspicious. Perhaps the heavens were punishing her for defying her parents’ will. Perhaps the red line of interest which ticked lower and lower collapsed the mortgage market and caused banks to tighten their nooses around lending.

Everything slid apart in the bitter winter of 2008. The victories she had sown and harvested fell away. Days passed without a single ring of the doorbell, and dust fell over the treatment table. She sold everything she could, all except that Qilin brocade, and what she did not spend on rent she spent on beer. Days passed in a colorless haze as the cheap alcohol created warmth inside her. She had risen so high and fallen so quickly; she could not bear it. Her drunkenness chased away her last faithful customers.

In the final week, they stopped providing electricity. It was January, six days away from Lunar New Year. Through the fogged glass, she saw mirages of Hong Kong’s festivities. She watched dragons and night parades and tasted lotus roots and prawns in the cracks of her teeth. Empty bottles glittered between the beige tiles like fireworks growing from the earth. Meanwhile, the needles rusted away, tips bitten by ginger rust.

On the first day of the Year of the Ox, a curious neighbor drunkenly wandered into the clinic to check on the disgraced Mistress. He found her sitting at her table, a frozen half-bottle of beer beside her. Her last breaths lingered above her cracked lips in shallow wisps long after she was gone, her hair turned the color of ice. Broken needles were scattered around her like decapitated thorns.

The brocade had been taken down, leaving the yellowish wall barren. All that remained of it was the scrap of gold fabric clutched in her fist, edges singed black.

—

A few years later, a twenty-three-year-old girl with tanned skin from the mainland arrived alone on the plane. She bought an office in a strip mall at the center of Chinatown. With it came an old treatment table that she modified into her first pedicure chair. Business might be difficult at first, but her unique designs were sure to attract Chinese and American clientele alike. Carrying many fears and hopes, she opened her nail salon.

针灸止痛: pain relief acupuncture

Qilin: a mythical horned, four-legged Chinese creature that symbolizes luck and prosperity

qi: vitality, life force

jīngmài (經脈): meridian channels

luòmài (絡脈): associated vessels

pǔtōnghuà (普通话): Mandarin

guǎngdōnghuà (广东话): Cantonese

了解到突发消息的备考生们面对这样的状况,一定要做好最后优化!刚刚接触赛事的同学也不要着急,可以看看更多的赛事规则赛事内容,提前为下个赛季做准备!

想了解更多背景提升项目

可扫上文二维码一对一咨询!